In "The Captain's Song" from the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera, The HMS Pinafore, after the Captain has explained to his crew all his personal prohibitions that make him such an exemplary captain (things like never getting sick at sea, never swearing, etc.), they sing this refrain to each other:

Sailors: What, never?

Captain: No, never!

Sailors: What, never?

Captain: Well, hardly ever!

Like the Captain, one of my personal teaching policies is that I

hardly ever give my students an assignment that I am not willing to do myself (or, at least, wasn't willing to do when I was at the same level of development) and/or haven't tried myself. I figure that if it's not interesting or valuable enough for me to do it, I shouldn't ask them to, and if I haven't tried it myself, how can I give them the best instruction on the matter? And while I've written a good bit of poetry in my time, I don't think I've ever written a concrete poem....which happens to be the topic I'm teaching this week.

So this past Sunday morning, I noticed something unusual as I was driving to our spiritual community, and so I ended up making a concrete poem out of the experience:

(OK, technically, this is actually a space poem, which shows movement through space related to the topic of the poem, rather than a concrete poem, which is supposed to take the shape of the subject. But we're covering both, so I think it still counts.)

I'm really glad I did it, because, like the I Spy poem, it is really much harder to do than it looks. Originally, the second stanza had varying numbers of words (from 9-11), and that just threw the entire composition off. So I had to find ways to express the same thing but with the same number of words while retaining the same syllable pattern. It was fun, but it ate up much more time than I expected (but, then, what doesn't?)

One thing that we've been doing in class is writing poetry after being inspired by music and/or art or photographs. And while the poem came from my experience (another thing we are discussing), the title was inspired by both. It is a twist on a Stephen Sondheim musical,

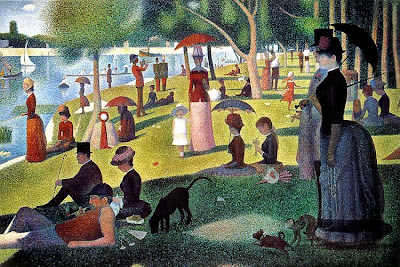

Sunday in the Park with George, which is about the artist, Georges Seurat, as he paints his most famous painting, "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" (well, it's really about a lot more then that, since it is an examination on the nature of art and artists and relationships, but that's for another blog).

Anyway, were I a visual artist, or even somewhat proficient with Photoshop, I would attempt a picture of what I see in my mind when I think of this poem, which is Seurat's painting:

EXCEPT I would replace all the people with geese, and add a few contemporary touches, like one of them playing with a video game, and, of course, a pizza. Wouldn't that be a fantastic image?

But, the point is, I think it is really great if we can teach students to use all their senses when writing poetry. It's great to come up with wonderful words, but it is good for those words to connect with an actual experience, to be inspired by or contain some elements of music (in my case, it's "Putting It All Together" from Sunday in the Park with George), and to create a visual image (like my Seurat geese). Not every poem needs to have ALL of those, but they should have at least one of these to generate some substance beyond just the words. And try it yourself--see if your poem isn't more fun and/or more meaningful to you when it includes one or more of those elements.

For a related post, see

A Concrete Poem on Catching Fire.

PS--My son wanted to be mentioned in this post, so I will just say that he read my draft and called it "a lovely poem," which I really appreciated hearing from him.